ISO 12108:2018

(Main)Metallic materials — Fatigue testing — Fatigue crack growth method

Metallic materials — Fatigue testing — Fatigue crack growth method

This document describes tests for determining the fatigue crack growth rate from the fatigue crack growth threshold stress-intensity factor range, ΔKth, to the onset of rapid, unstable fracture. This document is primarily intended for use in evaluating isotropic metallic materials under predominantly linear-elastic stress conditions and with force applied only perpendicular to the crack plane (mode I stress condition), and with a constant force ratio, R.

Matériaux métalliques — Essais de fatigue — Méthode d'essai de propagation de fissure en fatigue

General Information

Relations

Overview

ISO 12108:2018 - "Metallic materials - Fatigue testing - Fatigue crack growth method" specifies a standardized method to generate fatigue crack growth rate data for metallic materials. The standard covers testing from the fatigue crack growth threshold (ΔKth) up to the onset of rapid, unstable fracture. It is intended for predominantly linear‑elastic, mode I (opening mode) loading with a constant force ratio (R). ISO 12108:2018 defines specimen types, apparatus, precracking and test procedures, crack‑length measurement techniques, calculations and reporting requirements.

Key topics and technical requirements

- Scope and applicability: Focus on isotropic metallic materials under linear‑elastic conditions; tests assume force applied perpendicular to the crack plane (mode I) and constant R.

- Specimens and annexes: Normative annexes provide geometry and calibration for common specimens - Compact Tension (CT), Centre Crack Tension (CCT), Single Edge Notch Tension (SENT), Single Edge Notch Bend (SENB).

- Apparatus and precracking: Requirements for fatigue precracking to produce a representative crack starter, and guidance on specimen orientation and thickness limits to avoid large‑scale yielding, buckling or out‑of‑plane distortion.

- Test procedures: Procedures include constant‑force amplitude (K‑increasing) and K‑decreasing approaches for different crack growth rate regimes, plus guidance on crack‑growth rate data collection (da/dN versus ΔK).

- Crack length measurement: Visual and non‑visual methods (including electric potential difference) are covered, with guidance on measurement resolution, interruption, and dealing with bifurcation or out‑of‑plane cracking.

- Calculations and data analysis: Methods for converting crack length and cycle count into fatigue crack growth rate are specified, including secant and incremental polynomial methods, treatment of crack‑front curvature and determination of ΔK and ΔKth.

- Influencing factors: The standard highlights effects of residual stresses, crack closure, specimen thickness, waveform, frequency and environment on results and requires reporting these factors.

- Reporting: Detailed test report content is prescribed (material, specimen, precracking details, test conditions, analysis and presentation of results).

Applications and users

ISO 12108:2018 is used by:

- Materials and fatigue testing laboratories generating fatigue crack growth rate curves (da/dN vs ΔK)

- Fracture‑mechanics researchers and R&D teams characterizing crack propagation resistance

- Structural and design engineers using fracture mechanics to assess component life and damage tolerance

- Manufacturers and quality managers verifying material performance and compliance

Typical applications include fatigue life prediction, damage‑tolerance assessments, material selection, and validation of finite‑element fracture mechanics models.

Related standards

- Standards on fracture mechanics and stress‑intensity factor calibration (referenced generically within ISO 12108)

- ISO/TC 164 family standards on mechanical testing of metals and fatigue/toughness testing

Keywords: ISO 12108:2018, fatigue crack growth, metallic materials, fatigue testing, ΔK, stress‑intensity factor, da/dN, CT, SENT, SENB, fracture mechanics.

Standards Content (Sample)

INTERNATIONAL ISO

STANDARD 12108

Third edition

2018-07

Metallic materials — Fatigue testing —

Fatigue crack growth method

Matériaux métalliques — Essais de fatigue — Méthode d'essai de

propagation de fissure en fatigue

Reference number

©

ISO 2018

© ISO 2018

All rights reserved. Unless otherwise specified, or required in the context of its implementation, no part of this publication may

be reproduced or utilized otherwise in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, or posting

on the internet or an intranet, without prior written permission. Permission can be requested from either ISO at the address

below or ISO’s member body in the country of the requester.

ISO copyright office

CP 401 • Ch. de Blandonnet 8

CH-1214 Vernier, Geneva

Phone: +41 22 749 01 11

Fax: +41 22 749 09 47

Email: copyright@iso.org

Website: www.iso.org

Published in Switzerland

ii © ISO 2018 – All rights reserved

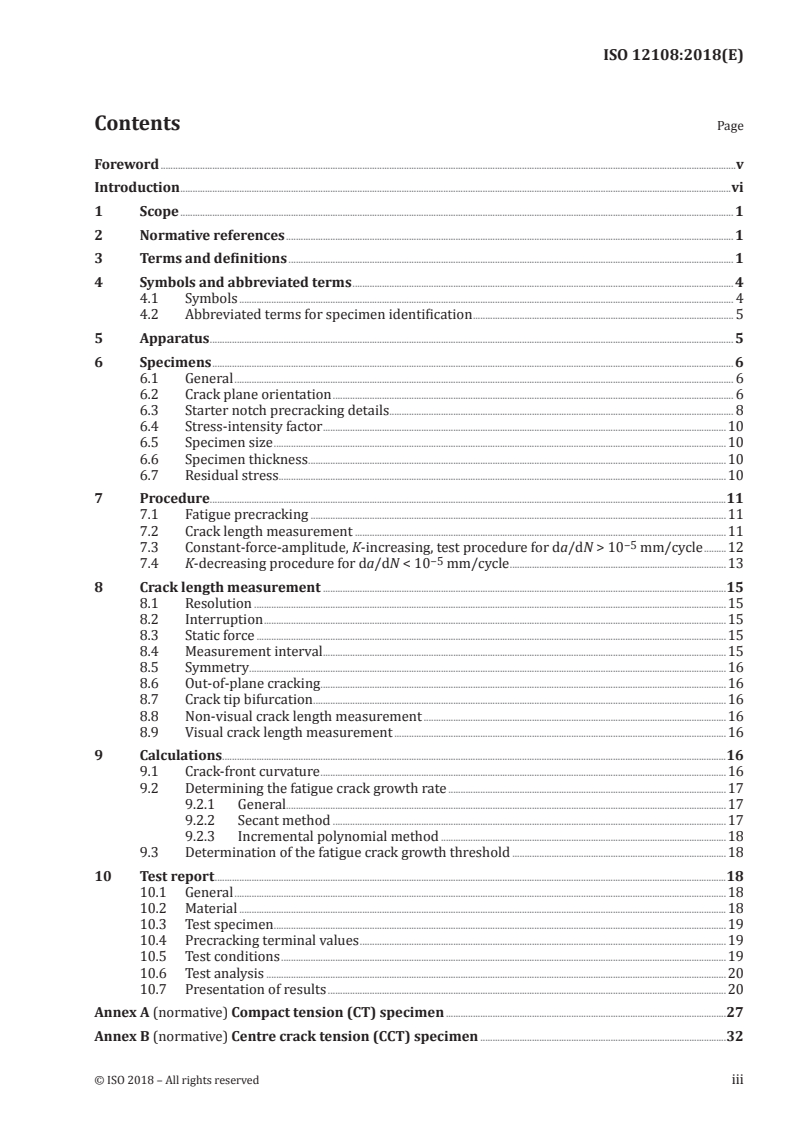

Contents Page

Foreword .v

Introduction .vi

1 Scope . 1

2 Normative references . 1

3 Terms and definitions . 1

4 Symbols and abbreviated terms . 4

4.1 Symbols . 4

4.2 Abbreviated terms for specimen identification . 5

5 Apparatus . 5

6 Specimens . 6

6.1 General . 6

6.2 Crack plane orientation . 6

6.3 Starter notch precracking details. 8

6.4 Stress-intensity factor .10

6.5 Specimen size .10

6.6 Specimen thickness .10

6.7 Residual stress . .10

7 Procedure.11

7.1 Fatigue precracking .11

7.2 Crack length measurement .11

−5

7.3 Constant-force-amplitude, Κ-increasing, test procedure for da/dN > 10 mm/cycle .12

−5

7.4 K-decreasing procedure for da/dN < 10 mm/cycle .13

8 Crack length measurement .15

8.1 Resolution .15

8.2 Interruption .15

8.3 Static force .15

8.4 Measurement interval .15

8.5 Symmetry.16

8.6 Out-of-plane cracking .16

8.7 Crack tip bifurcation .16

8.8 Non-visual crack length measurement .16

8.9 Visual crack length measurement .16

9 Calculations.16

9.1 Crack-front curvature .16

9.2 Determining the fatigue crack growth rate .17

9.2.1 General.17

9.2.2 Secant method .17

9.2.3 Incremental polynomial method .18

9.3 Determination of the fatigue crack growth threshold .18

10 Test report .18

10.1 General .18

10.2 Material .18

10.3 Test specimen .19

10.4 Precracking terminal values .19

10.5 Test conditions .19

10.6 Test analysis .20

10.7 Presentation of results .20

Annex A (normative) Compact tension (CT) specimen .27

Annex B (normative) Centre crack tension (CCT) specimen .32

Annex C (normative) Single edge notch tension (SENT) specimen .38

Annex D (normative) Single edge notch bend (SENB) specimens .41

Annex E (informative) Non-visual crack length measurement methodology — Electric

[9][12][36]

potential difference .48

Bibliography .51

iv © ISO 2018 – All rights reserved

Foreword

ISO (the International Organization for Standardization) is a worldwide federation of national standards

bodies (ISO member bodies). The work of preparing International Standards is normally carried out

through ISO technical committees. Each member body interested in a subject for which a technical

committee has been established has the right to be represented on that committee. International

organizations, governmental and non-governmental, in liaison with ISO, also take part in the work.

ISO collaborates closely with the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) on all matters of

electrotechnical standardization.

The procedures used to develop this document and those intended for its further maintenance are

described in the ISO/IEC Directives, Part 1. In particular the different approval criteria needed for the

different types of ISO documents should be noted. This document was drafted in accordance with the

editorial rules of the ISO/IEC Directives, Part 2 (see www .iso .org/directives).

Attention is drawn to the possibility that some of the elements of this document may be the subject of

patent rights. ISO shall not be held responsible for identifying any or all such patent rights. Details of

any patent rights identified during the development of the document will be in the Introduction and/or

on the ISO list of patent declarations received (see www .iso .org/patents).

Any trade name used in this document is information given for the convenience of users and does not

constitute an endorsement.

For an explanation on the voluntary nature of standards, the meaning of ISO specific terms and

expressions related to conformity assessment, as well as information about ISO's adherence to the

World Trade Organization (WTO) principles in the Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT) see the following

URL: www .iso .org/iso/foreword .html.

This document was prepared by Technical Committee ISO/TC 164, Mechanical testing of metals,

Subcommittee SC 4, Fatigue, fracture and toughness testing.

Any feedback or questions on this document should be directed to the user’s national standards body. A

complete listing of these bodies can be found at www .iso .org/members .html.

This third edition cancels and replaces the second edition (ISO 12108:2012), which has been technically

revised. The main changes compared to the previous edition are as follows:

— The document has been reorganized to move the formulae and drawings for each of the test

specimens from the main body of the document into a separate normative annex for each specimen.

— Guidance on the effects of residual stress on fatigue crack growth rate data has been expanded.

Introduction

This document is intended to provide specifications for generation of fatigue crack growth rate data.

Test results are expressed in terms of the fatigue crack growth rate as a function of crack-tip stress-

[15][16][17]

intensity factor range, ΔK, as defined by the theory of linear elastic fracture mechanics

[18][19][20]

. Expressed in these terms, the results characterize a material's resistance to subcritical

crack extension under cyclic force test conditions. This resistance is independent of specimen planar

geometry and thickness, within the limitations specified in Clause 6.

This document describes a method of subjecting a precracked notched specimen to a cyclic force. The

crack length, a, is measured as a function of the number of elapsed force cycles, N. From the collected

crack length and corresponding force cycles relationship, the fatigue crack growth rate, da/dN, is

determined and is expressed as a function of stress-intensity factor range, ΔK.

Materials that can be tested by this method are limited by size, thickness and strength only to the

extent that the material remains predominantly in an elastic condition during testing and that buckling

is precluded.

Specimen size can vary over a wide range. Proportional planar dimensions for six standard

configurations are presented. The choice of a particular specimen configuration can be dictated

by the actual component geometry, compression test conditions or suitability for a particular test

environment.

Specimen size is a variable that is subjective to the test material's 0,2 % proof strength and the

maximum stress-intensity factor applied during test. Specimen thickness can vary independently of the

planar size, within defined limits, so long as large-scale yielding is precluded and out-of-plane distortion

or buckling is not encountered. Any alternate specimen configuration other than those included in

this document can be used, provided there exists an established stress-intensity factor calibration

[21][22][23]

expression, i.e. stress-intensity factor geometry function, g (a/W) .

[24][25] [26][27]

Residual stresses , crack closure , specimen thickness, cyclic waveform, frequency and

environment, including temperature, can markedly affect the fatigue crack growth data but are in no

way reflected in the computation of ΔK, and so should be recognized in the interpretation of the test

results and be included as part of the test report. All other demarcations from this method should be

noted as exceptions to this practice in the final report.

−5

For crack growth rates above 10 mm/cycle, the typical scatter in test results generated in a single

[28] −5

laboratory for a given ΔK can be in the order of a factor of two . For crack growth rates below 10

mm/cycle, the scatter in the da/dN calculation can increase to a factor of 5 or more. To ensure the

correct description of the material's da/dN versus ΔK behaviour, a replicate test conducted with the

same test parameters is highly recommended.

[29]

Service conditions can exist where varying ΔK under conditions of constant K or K control

max mean

can be more representative than data generated under conditions of constant force ratio; however,

these alternate test procedures are beyond the scope of this document.

vi © ISO 2018 – All rights reserved

INTERNATIONAL STANDARD ISO 12108:2018(E)

Metallic materials — Fatigue testing — Fatigue crack

growth method

WARNING — This document does not address safety or health concerns, should such issues

exist, that can be associated with its use or application. The user of this document has the sole

responsibility to establish any appropriate safety and health concerns.

1 Scope

This document describes tests for determining the fatigue crack growth rate from the fatigue crack

growth threshold stress-intensity factor range, ΔK , to the onset of rapid, unstable fracture.

th

This document is primarily intended for use in evaluating isotropic metallic materials under

predominantly linear-elastic stress conditions and with force applied only perpendicular to the crack

plane (mode I stress condition), and with a constant force ratio, R.

2 Normative references

There are no normative references in this document.

3 Terms and definitions

For the purposes of this document, the following terms and definitions apply.

ISO and IEC maintain terminological databases for use in standardization at the following addresses:

— ISO Online browsing platform: available at https: //www .iso .org/obp

— IEC Electropedia: available at http: //www .electropedia .org/

3.1

crack length

a

crack size

linear measure of a principal planar dimension of a crack from a reference plane to the crack tip

3.2

cycle

smallest segment of a force-time or stress-time function which is repeated periodically

Note 1 to entry: The terms “fatigue cycle”, “force cycle” and “stress cycle” are used interchangeably. The letter N

is used to represent the number of elapsed cycles.

3.3

fatigue crack growth rate

da/dN

extension in crack length

3.4

maximum force

F

max

force having the highest algebraic value in the cycle, a tensile force being positive and a compressive

force being negative

3.5

minimum force

F

min

force having the lowest algebraic value in the cycle, a tensile force being positive and a compressive

force being negative

3.6

force range

ΔF

algebraic difference between the maximum and minimum forces in a cycle

ΔF = F − F

max min

3.7

force ratio

R

stress ratio

algebraic ratio of the minimum force or stress to the maximum force or stress in a cycle

R = F /F

min max

Note 1 to entry: R can also be calculated using the values of stress-intensity factors; R = K /K .

min max

3.8

stress-intensity factor

K

magnitude of the ideal crack-tip stress field for the opening mode force application to a crack in a

homogeneous, linear-elastically stressed body, where the opening mode of a crack corresponds to the

force being applied to the body perpendicular to the crack faces only (mode I)

Note 1 to entry: The stress-intensity factor is a function of applied force, crack length, specimen size and

geometry.

3.9

maximum stress-intensity factor

K

max

highest algebraic value of the stress-intensity factor in a cycle, corresponding to F and current

max

crack length

3.10

minimum stress-intensity factor

K

min

lowest algebraic value of the stress-intensity factor in a cycle, corresponding to F and current

min

crack length

Note 1 to entry: This definition remains the same, regardless of the minimum force being tensile or compressive.

For a negative force ratio (R < 0), there is an alternate, commonly used definition for the minimum stress-

intensity factor, K = 0. See 3.11.

min

3.11

stress-intensity factor range

ΔK

algebraic difference between the maximum and minimum stress-intensity factors in a cycle

ΔK = K − K

max min

Note 1 to entry: The variables ΔK, R and K are related as follows: ΔK = (1 − R) K .

max max

Note 2 to entry: For R ≤ 0 conditions, see 3.10 and 10.6.

2 © ISO 2018 – All rights reserved

Note 3 to entry: When comparing data developed under R ≤ 0 conditions with data developed under R > 0

conditions, it can be beneficial to plot the da/dN data versus K .

max

3.12

fatigue crack growth threshold stress-intensity factor range

ΔK

th

asymptotic value of ΔK for which da/dN approaches zero

Note 1 to entry: For most materials, the threshold is defined as the stress-intensity factor range corresponding to

−7

10 mm/cycle. When reporting ΔK , the corresponding lowest decade of da/dN data used in its determination

th

should also be included.

3.13

normalized K-gradient

C = (1/K) dK/da

fractional rate of change of K with increased crack length, a

C = 1/K (dK/da) = 1/K (dK /da) = 1/K (dK /da) = 1/ΔK (dΔK/da)

max max min min

3.14

K-decreasing test

test in which the value of the normalized K-gradient, C, is negative

Note 1 to entry: A K-decreasing test is conducted by reducing the stress-intensity factor either by continuously

shedding or by a series of steps, as the crack grows.

3.15

K-increasing test

test in which the value of C is positive

Note 1 to entry: For standard specimens, a constant force amplitude results in a K-increasing test where the

value of C is positive and increasing.

3.16

stress-intensity factor geometry function

g (a/W)

mathematical expression, based on experimental, numerical or analytical results, that relates the

stress-intensity factor to force and crack length for a specific specimen configuration

3.17

crack-front curvature correction length

a

cor

difference between the average through-thickness crack length and the corresponding crack length at

the specimen faces during the test

3.18

fatigue crack length

a

fat

length of the fatigue crack, as measured from the root of the machined notch

Note 1 to entry: See Figure 2.

3.19

notch length

a

n

length of the machined notch, as measured from the load line to the notch root

Note 1 to entry: See Figure 2.

3.20

specimen width

W

linear measure of a principal planar dimension of a specimen from a reference plane to the specimen edge

4 Symbols and abbreviated terms

4.1 Symbols

See Table 1.

Table 1 — Symbols and their designations

Symbol Designation Unit

Loading

−1

C Normalized K-gradient mm

E Tensile modulus of elasticity MPa

F Force kN

F Maximum force kN

max

F Minimum force kN

min

ΔF Force range kN

1/2

K Stress-intensity factor MPa·m

1/2

K Maximum stress-intensity factor MPa·m

max

1/2

K Minimum stress-intensity factor MPa·m

min

1/2

ΔK Stress-intensity factor range MPa·m

1/2

ΔK Initial stress-intensity factor range MPa·m

i

1/2

ΔK Fatigue crack growth threshold stress-intensity factor range MPa·m

th

N Number of cycles cycle

R Force ratio kN/kN

R Ultimate tensile strength at the test temperature MPa

m

R 0,2 % proof strength at the test temperature MPa

p0,2

Geometry

a Crack length or size measured from the reference plane to the crack tip mm

a Crack-front curvature correction length mm

cor

a Fatigue crack length measured from the notch root mm

fat

a Machined notch length mm

n

a Precrack length mm

p

B Specimen thickness mm

Hole diameter for CT, SENT or CCT specimen, loading tup diameter for bend

D mm

specimens

g(a/W) Stress-intensity factor geometry function unitless

h Notch height mm

W Specimen width measured from the reference plane to the specimen edge mm

(W − a) Uncracked ligament mm

Crack growth

da/dN Fatigue crack growth rate mm/cycle

Δa Change in crack length, crack extension mm

4 © ISO 2018 – All rights reserved

4.2 Abbreviated terms for specimen identification

CT Compact tension

CCT Centre cracked tension

SENT Single edge notch tension

SEN B3 Three-point single edge notch bend

SEN B4 Four-point single edge notch bend

SEN B8 Eight-point single edge notch bend

5 Apparatus

5.1 Testing machine.

5.1.1 The testing machine shall have smooth start-up and a backlash-free force train if passing through

zero force (tension – compression). Cycle to cycle variation of the peak force during precracking shall be

less than ±5 % and shall be held to within ±2 % of the desired peak force during the test. ΔF shall also

be maintained to within ±2 % of the desired range during test. A practical overview of test machines and

[36][37]

instrumentation is available .

5.1.2 If a dynamic force calibration is appropriate or required (e.g. by the purchaser), it should be

conducted according to ISO 4965-1. Dynamic force calibration is appropriate when inertial forces act

on the force transducer or any dynamic errors occur in the electronics of the force indicating system,

as described in ISO 4965-1. Test frequency and amplitude as well as grip mass can affect the inertial

forces acting on the force transducer. Examples for which dynamic force calibration can be appropriate

are configurations with the load cell on the moving piston or the part.

5.1.3 In terms of testing machine alignment, asymmetry of the crack front is an indication of

misalignment. For tension-compression testing, the length of the force train should be as short and stiff

as practical. Non-rotating joints should be used to minimize off-axis motion. It is important that adequate

attention be given to alignment of the testing machine and during machining and installation of the grips

in the testing machine. Regarding the relevance of alignment, a distinction shall be made between:

— Crack growth tests with rigid gripping and rigid load train which can also undergo compressive

forces and stresses (e.g. corner crack test pieces): a sufficient alignment of the load train can be

important for these test pieces to obtain correct and reproducible crack growth data, and

— Crack growth tests only with tensile load and fixed with bolts and using cardanic joints (e.g. CT-

specimens): due to the use of cardanic or similar joints in the load train alignment checks are not

necessary.

If an alignment check is appropriate (e.g. when using a rigid load train and grips) and required (e.g. by

the purchaser), it should be conducted according to ISO 23788 and using an alignment class 5 according

to ISO 23788. If alignment check is conducted, the results shall be reported.

5.1.4 Accuracy of the force measuring system shall be verified periodically in the testing machine.

The calibration for the force transducer shall be traceable to a national organization of metrology. The

force measuring system shall be designed for tension and compression fatigue testing and possess

great axial and lateral rigidity. The indicated force, as recorded as the output from the computer in an

automated system or from the final output recording device in a non-computer system, shall be within

the permissible variation from the actual force. The force transducer's capacity shall be sufficient to cover

the range of force measured during a test. Errors greater than 1 % of the difference between minimum

and maximum measured test force are not acceptable.

The force measuring system shall be temperature compensated, not have zero drift greater than

0,002 % of full scale, nor have a sensitivity variation greater than 0,002 % of full scale over a 1 °C

change. During elevated and cryogenic temperature testing, suitable thermal shielding/compensation

shall be provided to the force measuring system so it is maintained within its compensation range.

5.2 Cycle-counter.

An accurate digital device is required to count elapsed force cycles. A timer is to be used only as a

verification check on the accuracy of the counter. It is preferred that individual force cycles be counted.

−5

However, when the crack velocity is below 10 mm/cycle, counting in increments of 10 cycles is

acceptable.

5.3 Crack length measurement apparatus.

Accurate measurement of crack length during the test is very important. There are a number of

visual and non-visual apparati that can be used to determine the crack length. A brief description of a

variety of crack length measurement methods is included in Reference [14]. The required crack length

measurements are the average of the through-thickness crack lengths, as covered in 9.1.

6 Specimens

6.1 General

The proportional dimensions, formulae and procedures for the six standard specimen configurations

shall be as defined in Annexes A to D:

CT Compact tension Annex A

CCT Centre cracked tension Annex B

SENT Single edge notch tension Annex C

SEN B3 Three-point single edge notch bend Annex D

SEN B4 Four-point single edge notch bend Annex D

SEN B8 Eight-point single edge notch bend Annex D

This variety of specimen configurations is presented to accommodate the component geometry

available, test environment and force application conditions during a test. Machining tolerances

and surface finishes are also given in Figures 7 to 10. The CT, SEN B3 and SEN B4 specimens are

recommended for tension-tension test conditions only.

The specimen shall have the same metallurgical structure as the material for which the crack growth

rate is being determined. The test specimen shall be in the fully machined condition and in the final

heat-treated state that the material will see in service.

6.2 Crack plane orientation

The crack plane orientation, as related to the characteristic direction of the product, is identified in

Figure 1. The letter(s) preceding the hyphen represent the force direction normal to the crack plane;

the letter(s) following the hyphen represent the expected direction of crack extension. As specified

in ISO 3785 for wrought metals, the letter X always denotes the direction of principal processing

deformation, Y denotes the direction of least deformation and the letter Z is the third orthogonal

direction. If the specimen orientation does not coincide with the product's characteristic direction,

6 © ISO 2018 – All rights reserved

then two letters are used before and/or after the hyphen to identify the normal to the crack plane and/

or expected direction of crack extension.

NOTE For rectangular sections of wrought metals, a commonly used alternative designation system uses

the letters L to denote the direction of principal processing deformation (maximum grain flow), T to denote the

direction of least deformation and S for the third orthogonal direction.

a) Basic identification, longitudinal grain flow

b) Non-basic identification, longitudinal grain flow

c) Axial working direction, radial grain flow

d) Radial working direction, axial grain flow

a

Grain flow.

Figure 1 — Fracture plane orientation identification

6.3 Starter notch precracking details

The envelope and various acceptable machined notch configurations and precracking details for the

specimens shall be as specified in Figure 2.

Notch length, a , shall meet the requirements defined in each respective specimen annex. The

n

machined notches in the SENB and CCT specimens are determined by practical machining limitations;

the K-calibration does not have a notch size limitation.

8 © ISO 2018 – All rights reserved

The starter notch for the standard specimens can be made via electrical discharge machining (EDM),

milling, broaching or saw cutting. To facilitate precracking, the notch root radius should be as small as

practical, typically less than 0,2 mm. For aluminium, saw cutting the final 0,5 mm starter notch depth

with a jeweller’s saw is acceptable.

Crack length shall be measured from the reference plane.

Notch height, h, should be minimized and shall be less than or equal to the maximum notch height.

A hole of radius r < 0,05W is allowed for ease of machining the notch in a CCT specimen.

a

Reference plane.

b

Root radius.

Maximum notch height Minimum precrack length

h a

p

≤1 mm for W ≤ 25 a ≥ a + h, or

p n

W/16 for W > 25 a ≥ a + 1 mm, or

p n

a ≥ a + 0,1B, whichever is greater

p n

a ≥ 0,2W for CT only

p

Figure 2 — Notch detail and minimum fatigue precracking requirements

6.4 Stress-intensity factor

The stress-intensity factor for all standard specimen configurations is calculated using Formula (1):

F a

K = g (1)

12/

W

BW

The stress-intensity factor geometry function, g(a/W), for each standard specimen configuration is

calculated using the formulae shown in the specific specimen annex.

6.5 Specimen size

For the test results to be valid, it is required that the specimen remain predominantly in a linear-

elastic stress condition throughout the test. The specimen width, W, and thickness, B, can be varied

independently within the limits covered in 6.6. The smallest specimen to meet these criteria, based on

[35]

experimental results, varies with each specimen configuration .

The minimum uncracked ligament that circumvents large scale yielding varies with specimen

configuration and is a function of the material’s 0,2 % proof strength.

6.6 Specimen thickness

Specimen thickness, B, can be varied independently of specimen width, W, for the specimen

configurations, within the limits for buckling and through-thickness crack-front curvature

considerations. It is recommended that the selected specimen thickness be similar to that of the product

under study.

6.7 Residual stress

Residual stress in a material that has not been fully stress relieved can influence the crack propagation

[24][25][52]

rate considerably .

Example product forms that can be difficult to fully stress relieve and that can contain residual stress

include die forged, extruded or cast materials, as well as weldments. In addition, worked or formed

parts can contain intentionally induced residual stresses. When test specimens are extracted from

material that contains residual stress, redistribution often leads to specimens with a different residual

stress distribution than the original host material. Further, different specimen sizes and different

specimen types most likely have different residual stress distributions when machined from similarly

processed material and extracted from similar locations.

The influence of residual stress often leads to bias in the da/dN fatigue crack growth rates. For

instance, compressive residual stress can cause premature crack closure during a test, leading to FCG

rates biased much lower than would be expected for residual stress free material at the same applied

stress-intensity factor range and force ratio. Conversely, tensile residual stress can reduce the effects

of crack closure, leading to FCG rates biased higher than otherwise expected. When the residual stress

field is known for a test specimen, the stress-intensity factor due to the residual stress field can be

[23][24] [24]

estimated and has been used along with simple superposition models to estimate the effects

of the residual stress on the crack tip driving force (range and force ratio) and on resulting FCG rates.

However, a variety of confounding influences such as redistribution and plastic shake-down, among

others, can create significant challenges to partitioning the effects of residual stress from FCG rate

[52]

data .

Indications of residual stress include: machining distortion during specimen preparation, unexpectedly

slow or fast crack growth during precracking, excessive crack front curvature and crack growth

[25]

asymmetry .

The influence of residual stress on through-thickness crack front curvature and asymmetry can

be minimized by reducing the B/W ratio to minimize the variation in residual stresses through the

[25]

thickness . Reduced specimen size can also reduce the influence of residual stress; however, reduced

10 © ISO 2018 – All rights reserved

specimen size has other consequences, such as restricted ΔK range due to plasticity and net section

validity compared with larger specimens. When the residual stress field is expected to be asymmetric,

the edge crack configurations (CT or SEN specimens) can be a better choice than the CCT specimen

because an asymmetric residual stress distribution in a CCT specimen can lead to asymmetric (and

thus invalid) crack growth for the two crack tips.

7 Procedure

7.1 Fatigue precracking

The purpose of precracking is to provide a straight and sharp fatigue crack of sufficient length so

that the K-calibration expression is no longer influenced by the machined starter notch and that the

subsequent fatigue crack growth rate is not influenced by a changing crack front shape or precracking

force history.

One practice is to initiate the fatigue crack at the lowest possible maximum stress-intensity factor,

K , that is practical. If the test material's critical stress-intensity factor, which will cause fracture,

max

is approximately known, then the initial K for precracking can range from 30 % to 60 % of that. If

max

crack initiation does not occur within a block 30 000 to 50 000 load cycles, then K can be increased

max

by 10 % and the block of load cycles repeated. The final K for precracking shall not exceed the

max

initial K for either a K-increasing constant amplitude measurement or a K-decreasing threshold

max

measurement.

Frequently, a stress-intensity factor, greater than the K used in the test, needs to be used for crack

max

initiation. In this case, the maximum force shall be stepped down to meet the above criteria. When

manually controlling precracking, the recommended stress-intensity factor drop for each step is less

than 10 % of K . In addition, it is recommended that, between each stress-intensity factor reduction,

max

[9]

the crack extend by at least the value given in Formula (2) :

K

max( j−1)

Δa = (2)

j

π R

p02,

where K is the maximum terminal stress-intensity factor of the previous step. Alternatively,

max( j−1)

between each stress-intensity factor reduction, the crack extension can be limited Δa ≥ 0,50 mm.

When test data are to be generated for a high force ratio, it can be more convenient to precrack at a

lower K and force ratio than the initial test conditions.

max

The precracking apparatus shall apply the force symmetrical to the specimen’s notch and accurately

maintain the maximum force to within 5 %. A centre cracked panel shall also be symmetrically stressed

across the width, 2W. Any frequency that accommodates maintaining the force accuracy specified in 5.1

is acceptable.

The precrack shall meet the symmetry and out-of-plane cracking requirements as described in 7.2.

7.2 Crack length measurement

The requirements for measurement accuracy, frequency and validity are covered in Clauses 8 and 9

for the various specimen configurations and test procedures that follow. When surface measurements

are used to determine the crack length, it is recommended that both the front and back surface traces

be measured. If the front to back crack length measurements vary by more than 0,25B and, for a CCT

specimen, if the side-to-side symmetry of the two crack lengths varies in length by more than 0,025W,

then the precrack is not suitable and test data would be invalid under this test method. In addition,

if the precrack departs from the plane of symmetry beyond the corridor, defined by planes 0,05W on

either side of the specimen's plane of symmetry containing the notch root(s), the data would be invalid.

See Figure 3.

a

Reference plane.

b

Machined notch (length = a ).

n

Figure 3 — Out-of-plane-cracking validity corridor

−5

7.3 Constant-force-amplitude, Κ-increasing, test procedure for da/dN > 10 mm/cycle

−5

This procedure is appropriate for generating fatigue crack growth rate data above 10 mm/cycle.

Testing shall start at a K or stress-intensity factor range, ΔK, equal to or greater than that used for

max

the final crack extension while precracking. After stepping the maximum precracking force down to be

equal or less than that corresponding to the lowest K in the range over which fatigue crack growth

max

rate data will be generated, it is preferred that the force range be held constant as is the force ratio

and frequency. The maximum stress-intensity factor will increase with crack extension and should be

allowed to increase to equal or exceed the greatest K in the range over which data will be generated.

max

Several suggestions, aimed at minimizing transient effects while using this K-increasing procedure,

follow. If test variables are to be changed, K shall be increased rather than decreased in order to

max

preclude the retardation effects attributable to the previous force history.

— Transient effects can also occur following a change in K or the force ratio. An increase of 10 % or

min

less in K and/or K usually minimizes the transient effect reflected in the fatigue crack growth

max min

rate. Following a change in force conditions, sufficient crack extension shall be allowed to occur in

order to re-establish a steady-state crack growth rate before the ensuing test data are accepted as

valid under this test practice.

— The amount of crack extension required is dependent on many variables, e.g. percentage of force

change, the test material and heat treatment condition.

— When environmental effects are present, the amount of crack extension required to re-establish the

steady-state growth rate can increase beyond that required in a benign environment.

— Test interruptions shall be kept to a minimum. If the test is interrupted, a change in growth rate

can occur upon resumption of cycling. The test data immediately following the interruption shall be

12 © ISO 2018 – All rights reserved

considered invalid if there is a significant demarcation in the crack velocity from the steady-state

growth rate immediately preceding the suspension of cycling.

— The sphere of influence of the transient effect can increase with the steady-state force applied to the

specimen during the suspension of dynamic force cycling.

−5

7.4 K-decreasing procedure for da/dN < 10 mm/cycle

This K-decreasing procedure can result in different crack growth rates dependent on the test

K-gradient, C. It is the user's responsibility to verify that the crack growth rates are not sensitive to the

test K-gradient, C.

Testing shall start at a K or stress-intensity factor range, ΔK, equal to or greater than that used

max

for the final crack extension while precracking. Following crack extension, the stress-intensity factor

range is stepped down, o

...

Frequently Asked Questions

ISO 12108:2018 is a standard published by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO). Its full title is "Metallic materials — Fatigue testing — Fatigue crack growth method". This standard covers: This document describes tests for determining the fatigue crack growth rate from the fatigue crack growth threshold stress-intensity factor range, ΔKth, to the onset of rapid, unstable fracture. This document is primarily intended for use in evaluating isotropic metallic materials under predominantly linear-elastic stress conditions and with force applied only perpendicular to the crack plane (mode I stress condition), and with a constant force ratio, R.

This document describes tests for determining the fatigue crack growth rate from the fatigue crack growth threshold stress-intensity factor range, ΔKth, to the onset of rapid, unstable fracture. This document is primarily intended for use in evaluating isotropic metallic materials under predominantly linear-elastic stress conditions and with force applied only perpendicular to the crack plane (mode I stress condition), and with a constant force ratio, R.

ISO 12108:2018 is classified under the following ICS (International Classification for Standards) categories: 77.040.10 - Mechanical testing of metals. The ICS classification helps identify the subject area and facilitates finding related standards.

ISO 12108:2018 has the following relationships with other standards: It is inter standard links to ISO 12108:2012. Understanding these relationships helps ensure you are using the most current and applicable version of the standard.

You can purchase ISO 12108:2018 directly from iTeh Standards. The document is available in PDF format and is delivered instantly after payment. Add the standard to your cart and complete the secure checkout process. iTeh Standards is an authorized distributor of ISO standards.

Questions, Comments and Discussion

Ask us and Technical Secretary will try to provide an answer. You can facilitate discussion about the standard in here.

Loading comments...