ISO/TS 16829:2017

(Main)Non-destructive testing — Automated ultrasonic testing — Selection and application of systems

Non-destructive testing — Automated ultrasonic testing — Selection and application of systems

The information in ISO/TS 16829:2017 covers all kinds of ultrasonic testing on components or complete manufactured structures for either correctness of geometry, for material properties (quality or defects), and for fabrication methodology (e.g. weld testing). ISO/TS 16829:2017 enables the user, along with a customer specification, or a given test procedure or any standard or regulation to select: - ultrasonic probes, probe systems and controlling sensors; - manipulation systems including controls; - electronic sub-systems for the transmission and reception of ultrasound; - systems for data storage and display; - systems and methods for evaluation and assessment of test results. With regard to their performance, ISO/TS 16829:2017 also describes procedures for the verification of the performance of the selected test system. This includes - tests during the manufacturing process of products (stationary testing systems), and - tests with mobile systems.

Essais non destructifs — Contrôle automatisé par ultrasons — Sélection et application des systèmes

General Information

Standards Content (Sample)

TECHNICAL ISO/TS

SPECIFICATION 16829

First edition

2017-10

Non-destructive testing — Automated

ultrasonic testing — Selection and

application of systems

Essais non destructifs — Contrôle automatisé par ultrasons —

Sélection et application des systèmes

Reference number

©

ISO 2017

© ISO 2017, Published in Switzerland

All rights reserved. Unless otherwise specified, no part of this publication may be reproduced or utilized otherwise in any form

or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, or posting on the internet or an intranet, without prior

written permission. Permission can be requested from either ISO at the address below or ISO’s member body in the country of

the requester.

ISO copyright office

Ch. de Blandonnet 8 • CP 401

CH-1214 Vernier, Geneva, Switzerland

Tel. +41 22 749 01 11

Fax +41 22 749 09 47

copyright@iso.org

www.iso.org

ii © ISO 2017 – All rights reserved

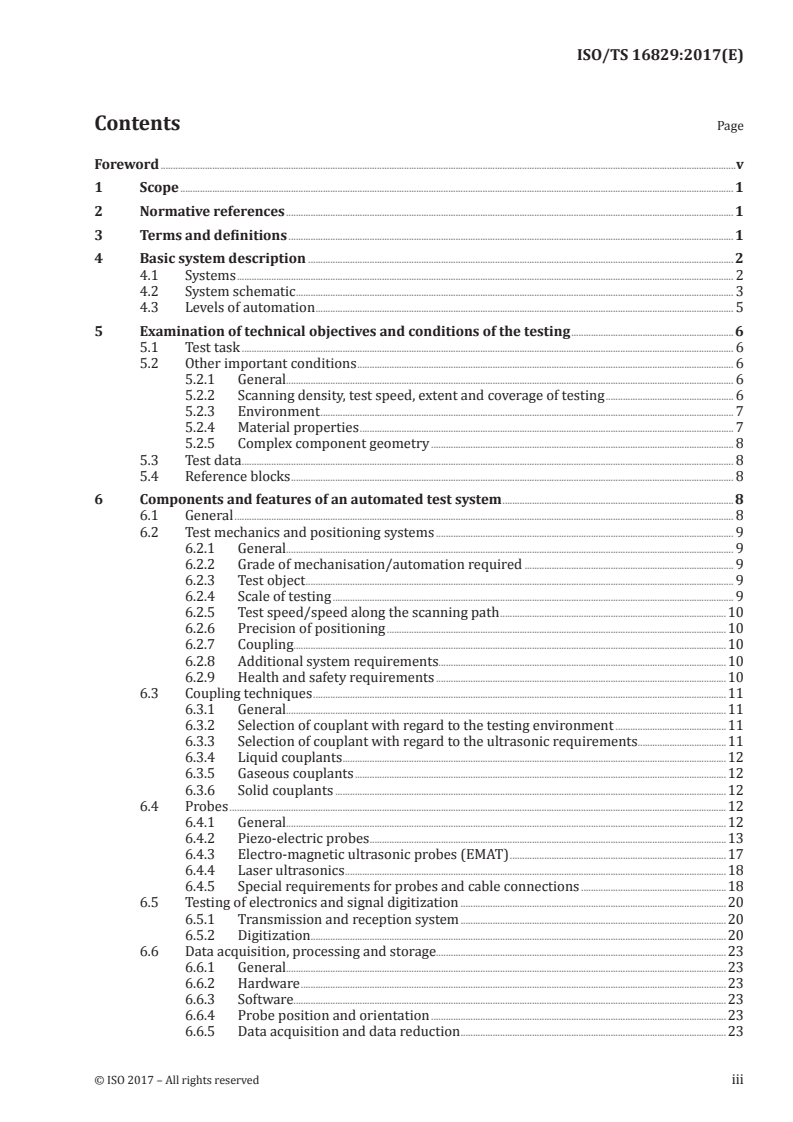

Contents Page

Foreword .v

1 Scope . 1

2 Normative references . 1

3 Terms and definitions . 1

4 Basic system description . 2

4.1 Systems . 2

4.2 System schematic . 3

4.3 Levels of automation . 5

5 Examination of technical objectives and conditions of the testing . 6

5.1 Test task . 6

5.2 Other important conditions . 6

5.2.1 General. 6

5.2.2 Scanning density, test speed, extent and coverage of testing . 6

5.2.3 Environment . 7

5.2.4 Material properties . 7

5.2.5 Complex component geometry . 8

5.3 Test data . 8

5.4 Reference blocks . 8

6 Components and features of an automated test system . 8

6.1 General . 8

6.2 Test mechanics and positioning systems . 9

6.2.1 General. 9

6.2.2 Grade of mechanisation/automation required . 9

6.2.3 Test object . 9

6.2.4 Scale of testing . 9

6.2.5 Test speed/speed along the scanning path .10

6.2.6 Precision of positioning .10

6.2.7 Coupling.10

6.2.8 Additional system requirements.10

6.2.9 Health and safety requirements .10

6.3 Coupling techniques .11

6.3.1 General.11

6.3.2 Selection of couplant with regard to the testing environment .11

6.3.3 Selection of couplant with regard to the ultrasonic requirements.11

6.3.4 Liquid couplants .12

6.3.5 Gaseous couplants .12

6.3.6 Solid couplants .12

6.4 Probes .12

6.4.1 General.12

6.4.2 Piezo-electric probes .13

6.4.3 Electro-magnetic ultrasonic probes (EMAT) .17

6.4.4 Laser ultrasonics .18

6.4.5 Special requirements for probes and cable connections .18

6.5 Testing of electronics and signal digitization .20

6.5.1 Transmission and reception system .20

6.5.2 Digitization.20

6.6 Data acquisition, processing and storage.23

6.6.1 General.23

6.6.2 Hardware .23

6.6.3 Software.23

6.6.4 Probe position and orientation .23

6.6.5 Data acquisition and data reduction .23

6.6.6 Data storage .25

6.7 Presentation and evaluation of data .25

6.7.1 Presentation of data .25

6.7.2 Evaluation of data .25

6.8 System check .26

7 Execution of test .26

7.1 System set-up .26

7.2 Performing the test.27

7.3 Management of NDT data .27

Bibliography .28

iv © ISO 2017 – All rights reserved

Foreword

ISO (the International Organization for Standardization) is a worldwide federation of national standards

bodies (ISO member bodies). The work of preparing International Standards is normally carried out

through ISO technical committees. Each member body interested in a subject for which a technical

committee has been established has the right to be represented on that committee. International

organizations, governmental and non-governmental, in liaison with ISO, also take part in the work.

ISO collaborates closely with the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) on all matters of

electrotechnical standardization.

The procedures used to develop this document and those intended for its further maintenance are

described in the ISO/IEC Directives, Part 1. In particular the different approval criteria needed for the

different types of ISO documents should be noted. This document was drafted in accordance with the

editorial rules of the ISO/IEC Directives, Part 2 (see www.iso.org/directives).

Attention is drawn to the possibility that some of the elements of this document may be the subject of

patent rights. ISO shall not be held responsible for identifying any or all such patent rights. Details of

any patent rights identified during the development of the document will be in the Introduction and/or

on the ISO list of patent declarations received (see www.iso.org/patents).

Any trade name used in this document is information given for the convenience of users and does not

constitute an endorsement.

For an explanation on the voluntary nature of standards, the meaning of ISO specific terms and

expressions related to conformity assessment, as well as information about ISO's adherence to the

World Trade Organization (WTO) principles in the Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT) see the following

URL: www.iso.org/iso/foreword.html.

This document was prepared by Technical Committee ISO/TC 135, Non-destructive testing,

Subcommittee SC 3, Ultrasonic testing.

ISO/TS 16829 is based on technical report CEN/TR 15134:2005.

TECHNICAL SPECIFICATION ISO/TS 16829:2017(E)

Non-destructive testing — Automated ultrasonic testing —

Selection and application of systems

1 Scope

The information in this document covers all kinds of ultrasonic testing on components or complete

manufactured structures for either correctness of geometry, for material properties (quality or defects),

and for fabrication methodology (e.g. weld testing).

This document enables the user, along with a customer specification, or a given test procedure or any

standard or regulation to select:

— ultrasonic probes, probe systems and controlling sensors;

— manipulation systems including controls;

— electronic sub-systems for the transmission and reception of ultrasound;

— systems for data storage and display;

— systems and methods for evaluation and assessment of test results.

With regard to their performance, this document also describes procedures for the verification of the

performance of the selected test system.

This includes

— tests during the manufacturing process of products (stationary testing systems), and

— tests with mobile systems.

2 Normative references

The following documents are referred to in the text in such a way that some or all of their content

constitutes requirements of this document. For dated references, only the edition cited applies. For

undated references, the latest edition of the referenced document (including any amendments) applies.

ISO 5577, Non-destructive testing — Ultrasonic testing — Vocabulary

3 Terms and definitions

For the purposes of this document, the terms and definitions given in ISO 5577 apply.

ISO and IEC maintain terminological databases for use in standardization at the following addresses:

— ISO Online browsing platform: available at http://www.iso.org/obp

— IEC Electropedia: available at http://www.electropedia.org/

4 Basic system description

4.1 Systems

There are two major applications for automated ultrasonic testing systems:

a) detection and evaluation of material defects (e.g. cracks, porosity, geometry);

b) measurement and evaluation of material properties (e.g. sound velocity, scattering).

Essential components of an automated test system are:

a) mechanically positioned and controlled ultrasonic probes and/or test objects;

b) automatic data acquisition for the ultrasonic signals;

c) acquisition and storage of probe positions in relation to the ultrasonic signals;

d) storage of test results.

A test system usually consists of several individually identifiable components. These are:

a) manipulators for probes or test objects;

b) probes and cables;

c) supply (pre-wetting), application and removal of the couplant;

d) electronic ultrasonic sub-systems;

e) data acquisition and processing devices;

f) data evaluation and display devices;

g) system controls;

h) sorting and marking of tested objects.

The complexity of a test system depends on the scope of the test and application of the system.

Test systems may be divided into stationary and mobile devices.

Examples of stationary test systems are testing machines:

— for the continuous testing of steel products, e.g. billets, plates, tubes, rails;

— for the testing of components, e.g. steering knuckles, rollers, balls, bolts, pressure cylinders;

— for the testing of composite materials, such as aerospace structures, e.g. complete wings made of

composite materials, CRFP and GFRP components;

— for the testing of random samples (batch test) in a process accompanying production checks, e.g.

testing for hydrogen induced cracking in steel samples.

Examples of mobile test systems are test rigs:

— for pre-service and in-service testing of components, e.g. valves, vessels, bolts, turbine parts;

— for pre-service and in-service inspection of vehicles;

— for pre-service and in-service testing of pipelines, e.g. oil or gas pipelines;

— ultrasonic testing of rails in railway tracks.

The test systems can be single or multichannel systems.

2 © ISO 2017 – All rights reserved

The complexity of the manipulator of the system depends on the examination task.

The complexity of the data acquisition and evaluation system depends on the number of test channels,

on the required test speed, and on other test requirements.

4.2 System schematic

The essential components of an automated ultrasonic scanning system are shown in Figure 1. More

detailed descriptions can be found elsewhere in this document. A detailed description of the individual

functions is given in Clause 5.

Key

1 probe no 1 4 data lines

2 probe no 2 5 control line

3 signal lines 6 control line/position data

Figure 1 — System schematic

The probe position shall be determined and be recorded together with the ultrasonic data. This can be

achieved by using encoders, ultrasound, or video techniques.

The most simple ultrasonic system uses only one probe (Figure 2).

Figure 2 — Simple system with one probe

In order to fulfil more complex test requirement, the system can include several hundred probes, e.g. in

a pig for pipeline testing, see Figure 3.

The ultrasonic sub-system is the main component of the complete test system. Figure 4 shows a block

diagram of the basic electronic components of the ultrasonic sub-system. Depending on the required

complexity, the ultrasonic sub-system can be made from one module for a single-channel system or

multiple modules for multi-channel systems. These can be self-contained modules, computer plug-in

cards, or rack mounted electronic systems.

Figure 3 — Probe assembly of an intelligent pig for use on a 40-inch-diameter pipeline

Figure 4 — Block diagram of the electronics of the ultrasonic sub-system

Some digital systems used for testing provide acquisition and storage of full RF ultrasonic signals. This

mode offers the most information compared to other acquisition methods.

In order to reduce the time for testing, data processing and storage, other methods use data reduction

techniques such as signal peak evaluation. For many applications, this provides a perfectly adequate

level of data for the purposes of the testing.

Methods for data reduction are described in 6.6.5.2.

The data, which are transferred from the ultrasonic unit to the data acquisition unit, are referred to as

test data.

In the data processing unit, the test data are processed in a way which enables them to be visualized on

a display for the interpreter (user) performing the evaluation.

The data can be assessed and the test verified automatically during automated testing of objects.

In certain industrial sectors, the evaluation has to be performed by experienced test personnel, e.g. for

welds on vessels and pipelines, or for safety-critical components in the aerospace industry. In these

4 © ISO 2017 – All rights reserved

cases, the data processing unit has to provide images from the test data as a projection or sectional

image. Other tasks are possible by filtering of the data to remove unwanted information. This can be

achieved by software in a computer or by special hardware.

Data can be stored at different moments during the signal processing, as shown in Figure 1. If this is a

simple go/no go test, only the final test result needs be recorded. In contrast, during testing of safety-

critical components, the test data are stored together with any assessment result.

The control and synchronization of the individual system components is achieved by the system control.

This ensures that the proper test sequence is performed.

The system control also synchronizes the storage of the probe positioning data and the ultrasonic data.

In-process testing can provide automated sorting or marking of unacceptable test objects.

A practical example of a basic system for automated scanning is shown in Figure 1. The set-up of a

multi-channel test system is shown in Figure 5. This system has an XY-manipulator, and can be used for

testing of vessels and pipes.

Key

1 sector of testing 3 manipulator control

— online survey 4 ultrasonic electronics

— data acquisition 5 probe cable

2 sector of evaluation 6 position data

— test planning 7 motor control, encoder signals

— data acquisition 8 optional network link to ultrasonic electronics

— display 9 network interface

— assessment

— documentation

Figure 5 — Set-up of a multi-channel test system

4.3 Levels of automation

Various levels of automated testing are possible, ranging from simple probe movement assisted by

mechanical means through to fully automated acquisition and assessment of test data, and marking or

sorting of test objects.

5 Examination of technical objectives and conditions of the testing

5.1 Test task

The test task specifies the discontinuities or material properties that the test is intended to detect or to

measure.

The specification for the test system shall be designed within practical and economical viable limits,

with due consideration to the properties of the test object.

Any existing relevant normative documents shall be taken into consideration.

The technical limits of the test system are governed, by amongst other things, the following parameters:

a) overall signal-to-noise ratio of the ultrasonic sub-system;

b) bandwidth of the probe(s) and the ultrasonic sub-system;

c) spatial resolution of the sound beam(s).

The most important factor in all methods of automated scanning is the system’s dynamic lateral

resolution. The scanning pattern and the scanning speed shall be specified in accordance with the

sound beam dimensions as determined by a relevant reflector.

5.2 Other important conditions

5.2.1 General

The following conditions shall be considered for the specification of the test system:

a) requirements governed by the material properties, e.g. surface conditions and coupling

requirements;

b) standards, guidelines and other specifications;

c) limitations to perform the testing, e.g. by test environment, accessibility, weather conditions, and

power restrictions.

5.2.2 Scanning density, test speed, extent and coverage of testing

High speed testing is typical in automated scanning. This generates large amounts of data. If this is to

be automatically assessed, processing speed is a key issue.

There is a relationship between the gap between points of testing, speed of probe motion, pulse

repetition frequency, and speed of data acquisition. This relationship shall also consider the number of

channels.

If the probe is moved in a direction x and test data have to be taken equidistantly (either amplitude or

time-of-flight), the following condition shall be satisfied:

v< Δx * f/ n (1)

()

r

6 © ISO 2017 – All rights reserved

where

v is the scanning speed on the test object (mm/s);

Δx is the distance between test points (mm);

f is the pulse repetition frequency (Hz);

r

n is the number of pulses required per test point.

If the complete A-scan has to be acquired at each test point, Formula (2) applies:

vx≤Δ /t (2)

s

where

v is the relative speed between probe and test object (mm/s);

Δx is the distance between test points (mm);

t is the acquisition and storage time of an A-scan.

s

Normally, the transfer time of an A-scan to a storage medium (e.g. hard disk) is longer than the duration

(length) of an A-scan. In this case, t shall be equal to the slowest process step in the system.

s

5.2.3 Environment

Special consideration shall be given when the test system has to be used in harsh environments, e.g.:

— ionizing radiation;

— extreme temperature of the test object or the environment it is in;

— very high or low pressure in the environment (air or water pressure);

— aggressive atmosphere;

— areas at risk of explosion.

5.2.4 Material properties

Material properties may cause problems in performing an ultrasonic test. The following material

properties may cause problems:

— coarse grain structure (castings, austenitic steel, and concrete);

— inhomogeneous structure (varying structure in the same object);

— anisotropy (texture of wrought and forged products, columnar crystalline structure in austenitic

welds, and in fibre-reinforced composites);

— interfaces (dissimilar welds, composites, hardened zones).

These properties are often combined. They interfere with the propagation of the sound waves and may

cause the following problems:

— spurious indications;

— errors in locating of indications;

— wave mode conversion;

— sensitivity variations;

— local zones, which are not tested.

By selecting suitable techniques, these problems may be reduced or eliminated. An example is the

testing of austenitic welds where the evaluation of the test results is often possible only after processing

of B-scans and C-scans, which may be compared with the pattern of indications from previous tests or

from tests on test blocks containing known reference reflectors.

5.2.5 Complex component geometry

On complex geometries, an A-scan alone is insufficient for the evaluation. In such cases, position related

B-scans or C-scans, as well as imaging, e.g. synthetic aperture focusing techniques (SAFT), holography

or tomography, shall be considered.

These images, produced from time-of-flight and amplitude information (data), enable differentiation

between indications caused by geometry and those caused by discontinuities. Pattern recognition may

also be used to detect items of interest.

EXAMPLE For the testing of the spherical heads and bottom sections of nuclear pressure, vessels, very

often array probes, are used. These run on the spherically curved surface on predetermined tracks between

the nozzles for control and measuring rods. Testing for cracks on the inner surfaces is done by varying the skew

and beam angles of the probes. B-scans from these tracks running parallel to each other are then compared. It is

simple to differentiate between indications from cracks and from geometry.

5.3 Test data

The collected data shall be extensive enough to enable an assessment according to the required test

specification.

5.4 Reference blocks

It is recommended to use a set of reference blocks representative of the test object to ensure the

sensitivity and suitability of the overall system. The reference blocks shall have acoustical properties

same or similar to the tested material. The blocks shall contain reference reflectors that represent the

various discontinuities that need to be detected.

The reference reflectors allow to determine the detectability of a particular type of discontinuity and

the limits of detection.

The overall system should be checked with the reference blocks at regular intervals to maintain the

reliability of testing.

6 Components and features of an automated test system

6.1 General

The requirements on any individual test system are dictated by the application. The set-up and the

operation mode are determined by the technical objectives of the test technique and all prevailing

conditions.

Selection of any single component of the system is based on the test task and its ability for achieving the

desired test results.

Major characteristics of a test system are discussed in the following subclauses.

8 © ISO 2017 – All rights reserved

6.2 Test mechanics and positioning systems

6.2.1 General

Automated ultrasonic testing requires a movement of probe(s) and test object relative to each other. The

probe guidance mechanism provides the spatial relationship between the probe(s) and the test object.

The probe position is usually determined by electro-mechanical and/or electronic means (position

encoders).

The control of the mechanism may also provide:

a) control/guidance of other sensors (manually or mechanically);

b) control/guidance of the test object;

c) synchronization between other sensors and the test object;

d) feeding and removal of the test objects;

e) supply, application, and removal of the couplant.

In mobile test systems. the mechanics usually move the probe in relation to the test object. In stationary

(fixed) test systems, the mechanics usually move the test object in relation to the probe. Stationary test

systems are usually integrated into the production process of the test object.

Some of the parameters that shall be considered when designing a test system:

6.2.2 Grade of mechanisation/automation required

Different grades might be:

a) mechanized or hand-operated guidance of the probes;

b) machine-operated mechanized guidance of the probes;

c) manual feeding and removal of the test objects;

d) mechanized or automated feeding and removal of the test objects;

e) automated guidance of the sensors when the test object is outside the production process;

f) automated guidance of the sensors when the test object is in the production process;

g) marking or sorting of the test objects after semi- or fully automated assessment.

6.2.3 Test object

a) shape;

b) material;

c) surface condition;

d) temperature.

6.2.4 Scale of testing

a) testing of the whole test object or only parts of it;

b) single or multiple tests on each test object.

6.2.5 Test speed/speed along the scanning path

The test speed is determined by the following parameters:

a) approach and reset period;

b) pulse repetition frequency;

c) sound path length;

d) single or multi-channel operation.

6.2.6 Precision of positioning

The following requirements determine the accuracy of positioning:

a) detection of specified discontinuities;

b) characterization of discontinuities (position and size);

c) reproducibility of the test results (precision of access).

For some applications, the accuracy of positioning is stipulated by standards and specifications.

6.2.7 Coupling

The mechanical system shall provide suitable and appropriate coupling for the ultrasonic waves (5.2),

with particular concern to:

a) compatibility of couplant and test object (corrosion);

b) pressure;

c) temperature of the test object;

d) distance between the probe(s) and the test object;

e) viscosity of couplant;

f) supply application and removal of the coupling medium.

6.2.8 Additional system requirements

Consideration shall be given to the system’s actual mechanical condition:

a) environmental conditions;

b) availability (wear resistance);

c) life cycle;

d) maintainability/repairability;

e) long-term availability of the control software and firmware.

6.2.9 Health and safety requirements

All relevant health and safety regulations shall be observed.

10 © ISO 2017 – All rights reserved

6.3 Coupling techniques

6.3.1 General

A coupling medium (couplant) is necessary to enable the transfer of mechanical energy (vibration) from

the electro-mechanical transducer in the probe to the test object and back to the transducer.

There are other ultrasonic test techniques which operate without a coupling medium, e.g. with

ultrasound generated by electromagnetic transducers (EMAT) or by lasers. With these techniques, the

elastic vibrations are produced in the test object itself (5.3).

Media in all states can be used as couplant:

— gaseous state air

— liquid state water, oil, gel, etc.

— solid state metal foils, polymer foils, low melting crystals

However, not all of these are suitable for automated scanning systems. The most common couplants

are water, oil and emulsions, air if applicable or combined liquid/solid coupling (as by an ultrasonic

wheel probe).

6.3.2 Selection of couplant with regard to the testing environment

Conditions regarding the testing environment shall be considered when selecting couplants:

a) compatibility with the test object (e.g. avoidance of corrosion);

b) contamination of the test object by the couplant and decontamination/cleaning after testing where

necessary;

c) surface of the test object (e.g. flatness or roughness of the surface);

d) contour (complex geometry) and accessibility of the test object;

e) temperature of the test object with respect to the testing couplant and probe(s);

f) testing speed;

g) contamination of the couplant by the test object (e.g. radioactivity, dangerous chemicals);

h) environmental compatibility and disposal of the couplant.

6.3.3 Selection of couplant with regard to the ultrasonic requirements

The ultrasonic test itself shall be considered when selecting a couplant:

a) wave type used;

b) transferability of ultrasound by the couplant (distortion by bubbles or other scatterers);

c) frequency and bandwidth;

d) sound beam dimensions;

e) sound path in the delay line and in the test object;

f) test technique (through-transmission or pulse echo).

6.3.4 Liquid couplants

Suggestions for coupling techniques and applications are given in Table 1.

Table 1 — Various coupling techniques using liquids

Technique Description Guidance of the probes

a) Immersion technique test object completely immersed in liquid by external mechanics

b) Partial immersion liquid chamber or basin as immersion vessel for a by external mechanics,

technique part of the test object

by test object

c) Squirter technique sound is conducted via a long, free liquid jet by external mechanics

d) Jet technique liquid column is guided by nozzles close to the by external mechanics,

test object

by test object

e) Contact technique probe mounted in a shoe with a couplant filled slot by test object

between probe, probe shoe and test object

f) Flow gap coupling thin liquid film between probe and test object; by test object

probe floats

g) Direct contact technique direct contact of the probe shoe (with wear sole) by test object

with coupling pressure onto the test object while

the surface is wettened

Immersion techniques are particularly useful for testing single objects, the others are more suitable for

testing in a continuous production process.

6.3.5 Gaseous couplants

Using gaseous couplants, air for instance, offers particular flexibility on complex geometries and high

testing speed. It greatly simplifies couplant handling. Other problems arising with liquid couplants are

removed.

By the enormous differences of acoustic impedance between the gas and the test object result in high

signal losses, this necessitates the use of low frequency ultrasound (up to 1 MHz), usually in through-

transmission mode. Due to the low acoustic velocity of air testing, this is also restricted to low pulse

repetition rates.

6.3.6 Solid couplants

If required, a solid couplant can be used. A silicone foil offers dry coupling through a soft solid.

The wheel probe has an oil-filled tyre containing a probe transmitting sound waves radially, this offers a

combination of liquid and dry coupling. A slight wetting of the surface of the test object is advantageous

when using a wheel probe.

In practice using solid couplants is problematic since undesirable air/gas interface layers may arise

between the test object and the probe.

6.4 Probes

6.4.1 General

Probes contain transducers, usually piezo-electric devices, which convert electrical vibrations into

mechanical onces and vice-versa. Probes can therefore transmit ultrasonic waves as well as receive.

Other principles of ultrasound generation and reception are also available for non-destructive testing.

Examples are electro-magnetic ultrasonic (EMAT) probes and laser sources. With both techniques, the

surface layer of the test object forms part of the acoustic transducer.

12 © ISO 2017 – All rights reserved

In most cases, the pulse-echo technique is used. Short ultrasonic pulses are transmitted into the test

object. They are reflected, diffracted or scattered by discontinuities in the test object creating signals

which are then received as echoes. Some parameters of the received signals are extracted and used

for evaluation of the discontinuity. The amplitude of the signals can be used to evaluate the size of the

discontinuity. The time-of-flight of the signals enables the location of the discontinuity.

6.4.2 Piezo-electric probes

6.4.2.1 General

Piezo-electric probes can be specifically designed to suit the application. The geometry of the test

object, the area to be covered, the required resolution and the required wave type [longitudinal

(compressional) or transverse (shear)] shall be considered.

Besides the active piezo-electric transducer other important elements of a probe for pulse-echo testing

are a damping element, protective or matching layers, electrical matching circuits and the housing.

6.4.2.2 Piezo-electric transducer materials

Usually the piezo-electric transducer is a thin plate. The nominal frequency, f , of a transducer is

n

determined by the thickness, d, of this plate:

c

f= (3)

n

2d

where c is the sound velocity (longitudinal wave) in the piezo-electric material.

Because the frequency is inverse proportional to the thickness of the transducer plate the required

thickness decreases with increasing test frequency which in turn reduces the mechanical resistance of

the plate.

The piezo-electric transducer in most cases is made from ceramic material. The most common ceramics

is lead zirconate titanate (PZT), lead titanate (PbTiO ) and lead metaniobate (PbNb O ) are also used.

3 2 6

These ceramics are used for test frequencies up to 30 MHz.

The energy transmitted into the test object is determined by this quantity, but also by the acoustic

impedances of couplant and test object.

Piezo-electric foils made of polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) are also used as transducer material. Their

low acoustic impedance provides efficient transmission, particularly for the immersion technique.

These foils are rarely applied in the contact techniques. High frequencies can be achieved using PVDF

foils. Due to their flexibility, curved focusing transducers can easily be produced. However, their

disadvantage is their poor resistance to temperature (up to about 80 °C).

Composite piezo-materials are ceramic sticks or particles embedded in an epoxy resin matrix whose

properties as transducers are determined by the structure and the ratio of the components ceramic

and resin. They also exhibit low acoustic impedance, like foil transducers, but combined with the high

efficiency of piezo-ceramics. However, they have poor resistance to mechanical load and poor resistance

to temperature (up to about 100 °C).

6.4.2.3 Layout of piezo-electric probes

The transducer is coated with electrically conducting layers on both sides and basically offers a

capacitive load. The transmitted and received signals are conducted via wires connected to these

conductive layers.

There is usually a damping block (mass) behind the transducer which influences the vibrational

behaviour and the bandwidth of the probe housing the transducer. Mechanically attached to the piezo-

electric plate, the damping block also absorbs sound waves being emitted backwards. Interfering

reflections from within the damping mass are suppressed by specific shaping of the damping block.

When using piezo-electric materials with low acoustic impedances (foil transducers, composites, both

in contact techniques) with a plastic delay line located in front of the transducer (delay-line probes,

angle-beam probes with wedges, dual-element probes), damping blocks may be omitted.

Key

1 transducer 3 electrical matching circuit

2 transducer backing (damping block) 4 matching layer/protective layer

Figure 6 — Schematic of the set-up of a piezo-electric ultrasonic probe

The exterior probe face provides mechanical protection and sometimes acoustic matching.

Electrical impedance can be included in the probe to provide matching to the transmission and

receiving circuitry.

6.4.2.4 Probes for the contact technique

The simplest probe type is the normal-beam probe for the emission and reception of longitudinal waves

in the axial direction of the probe (Figure 6).

Angle-beam probes contain a plastic wedge allowing by refraction the transmission of sound waves at

a predetermined angle. The transducers of angle-beam probes very often are rectangular and usually

generate transverse waves in the test object. Angle-beam probes are used for the detection of reflectors

not detectable by a normal-beam probe. Weld testing is a typical field of application. The plastic wedges

necessary for the refraction of waves are wear parts, so angle-beam probes are built to enable easy

replacement of the wedge (Figure 7).

14 © ISO 2017 – All rights reserved

Key

1 transducer 5 wedge

2 absorber block 6 longitudinal wave

3 electrical matching circuit 7 refracted transverse wave

4 damping block

Figure 7 — Schematic of an ultrasonic angle-beam probe

Dual-transducer probes are designed with separate transducers for transmission and reception. Both

transducers are electrically independent and are separated acoustically by a barrier and a delay line.

This avoids cross-talk from transmitter to receiver. The transducers can be inclined towards one

another (the interior angle is known as roof angle) to achieve a focusing effect and an improvement

of re

...

Questions, Comments and Discussion

Ask us and Technical Secretary will try to provide an answer. You can facilitate discussion about the standard in here.

Loading comments...